How did you end up reading this text? If you’re reading it online, you may have clicked a link in an algorithmically generated list of recommendations or search results. Or maybe a friend sent you the link—after finding it in an algorithmically generated list. Whatever the chain of events that brought you here, it likely involved a system of information retrieval.

Such systems select a handful of choices from billions of possibilities. Their existence is inevitable: at any given time, we can only comprehend a small portion of an immense world. The problem is that the systems that filter the world are not designed for your benefit but for corporate profit. No word captures the dominant form of information consumption on the internet more aptly than “feed”—a ubiquitous term derived from an agrarian metaphor. As in animal husbandry, your information diet is engineered to maximize the yield of a business operation.

If Silicon Valley’s PR departments claim that their products simply “find the most relevant, useful results in a fraction of a second, and present them in a way that helps you find what you’re looking for”—this is how Google describes its search algorithms on its website—executives and shareholders know better. They know that the whole point of the business is to get paid to show you things that you’re not looking for: ads.

The conflict of interest between advertisers and users has always been evident to the designers of commercial search engines. In 1998, a few months before the incorporation of Google, graduate students Sergey Brin and Lawrence Page presented their prototype of a web search engine at an academic conference. In an appendix to their paper, they commented, “We expect that advertising funded search engines will be inherently biased towards the advertisers and away from the needs of the consumers.” Indeed. More than two decades after this prophecy, all major search engines, Google first among them, now operate precisely on the business model of surveillance-fueled targeted advertising.

These search engines’ algorithms are optimized for profit. The advertising industry governs the bulk of research and development in the field of information retrieval. Computer scientists and engineers often measure the “relevance” of potential results and test the “performance” of candidate algorithms according to evaluation benchmarks and validation data sets dictated by industry priorities. The predominant systems are designed to maximize ad revenues and “engagement” metrics such as “click-through rates.” Consequently, these systems tend to promote content that is already popular or similar to what users have seen or liked before. Whether the predictions of popularity and similarity are based on simple correlation and regression analysis or on complex machine learning models, the results tend to be predictable and like-minded.

No wonder the public sphere seems so impoverished in the digital age. The systems that manage the circulation of political speech were often originally designed to sell consumer products. This fact has momentous consequences. Recent scholarship has documented the disastrous effects of “surveillance capitalism,” and in particular how commercial search engines deploy “algorithms of oppression” that reinforce racist and sexist patterns of exposure, invisibility, and marginalization. These patterns of silencing the oppressed are so pervasive in the world that it may seem impossible to design a system that would not reproduce them.

But alternatives are possible. In fact, from the very beginnings of informatics—the science of information—as an institutionalized field in the 1960s, anti-capitalists have tried to imagine less oppressive, perhaps even liberatory, ways of indexing and searching information. Two Latin American social movements in particular—Cuban socialism and liberation theology—inspired experiments with different approaches to informatics from the 1960s to the 1980s. Taken together, these two historical moments can help us imagine new ways to organize information that threaten the capitalist status quo—above all, by facilitating the wide circulation of the ideas of the oppressed.

Struggle on the Library Front

What happens the day after the revolution? One answer is the reorganization of the library. In 1919, Lenin signed a resolution demanding that the People’s Commissariat of Enlightenment “immediately undertake the most energetic measures, firstly to centralize the library affairs of Russia, secondly to introduce the Swiss-American system.” Lenin presumably referred to the organization of the European libraries he had observed during his exile from Russia in the early 1900s. By imitating the “Swiss-American system,” the Bolshevik leader hoped to create a single state system of centralized control over the distribution of books and the development of collections.

Four decades later, Cuban revolutionaries also recognized the importance of what Soviet leaders like Nadezhda Krupskaya had once called the struggle “on the library front.” In the aftermath of the Cuban Revolution in 1959, Fidel Castro appointed librarian María Teresa Freyre de Andrade as the new director of the Jose Martí National Library in Havana. A lesbian and long-time dissident who had been exiled and jailed by the previous regimes, she had long been concerned with the politics of librarianship. In the 1940s, she had articulated her vision of a biblioteca popular, a “popular library,” distinct from a merely “public” one. Whereas the public library may be a “rather passive” one where “the book stands still on its shelf waiting for the reader to come searching for it,” the popular library is “eminently active” as it “makes extensive use of propaganda and uses different procedures to mobilize the book and make it go in search of the reader.”

After the revolution, Freyre de Andrade and her staff began to enact this vision. They brought books to the people by sending bibliobúses, buses that served as moving libraries, to rural areas where no libraries existed. They also began to develop a novel practice of revolutionary librarianship. Unlike with Lenin, the goal was not to imitate the organization of European libraries. In a 1964 speech, Freyre de Andrade argued that Cubans could not simply “copy what the English do in their libraries.” By doing so, “we would have a magnificent library, we would have it very well classified, we would provide a good service to many people, but we would not be taking an active part in what is the Revolution.”

How could librarians take an active part in the revolution? One answer was to gather and index materials that had been excluded or suppressed from library collections in the pre-revolutionary period, such as the publications of the clandestine revolutionary press of the 1950s. But librarians also became involved in a broader revolutionary project: Cuba’s effort to build its own computing industry and information infrastructure. This project ultimately led to a distinctive new field of information science, which inherited the revolutionary ideals of Cuban librarianship.

The Redistributing of Informational Wealth

Both the revolutionaries and their enemies recognized that information technology would be a strategic priority for the new Cuba. A former IBM executive recalls that “all of the foreign enterprises had been nationalized except for IBM Cuba,” since the “Castro government and most of the nationalized companies were users of IBM equipment and services.” But from 1961–62, IBM closed its Cuban branch, and the US government imposed a trade embargo that prevented Cuba from acquiring computer equipment. This meant that Cuba would be forced to develop its own computing industry, with help from other socialist countries in the Soviet-led Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (Comecon).

Between 1969 and 1970, a team at the University of Havana created a prototype of a digital computer, the CID-201, as well as an assembly language named LEAL, short for “Lenguaje Algorítmico” (Algorithmic Language), an acronym that also means “loyal.” The design of the CID-201 was based on the schematics found in the manual of the PDP-1, a computer manufactured by the US-based Digital Equipment Corporation. Because of the US-imposed trade embargo, the team could not buy the necessary electronic components in Europe, but eventually succeeded—with the help of a Cuban man of Japanese descent who worked as a merchant in Tokyo—in bringing the components from Japan inside more than ten briefcases.

Cuban mathematicians also wrote a computer program in LEAL for playing chess; one of the CID-201’s engineers recounts that the computer even played—and lost—a game against Fidel Castro. Starting in the 1970s, Cuba manufactured thousands of digital computers, and even exported some computer parts to other Comecon countries.

The rise of digital computing transformed Cuban librarianship. Freyre de Andrade welcomed the digital age, paraphrasing Marx and Engels to analogize computing to communism: “a specter is haunting the informational world, the specter of the computer; and let’s be pleased that this circumstance has come to move our field [of librarianship], giving us a challenge that makes [the field] even more interesting than it already was by itself.” Cubans studied the techniques of informatics mostly with Soviet textbooks translated into Spanish. They combined the computational methods they learned from these books with the revolutionary ideals of Cuban librarianship. This synthesis produced distinctive theories and practices that diverged substantially from those of both Western and Soviet informatics.

Consider the concept of “information laws,” a staple of informatics textbooks. A classic example is “Lotka’s law,” formulated in 1926 by Alfred J. Lotka, a statistician at Metropolitan Life Insurance Company in New York, who sought to compute the “frequency distribution of scientific productivity” by plotting publication counts of authors included in an index of abstracts of chemistry publications. He claimed that the distribution followed an “inverse square law,” i.e., “the number of persons making 2 contributions is about one-fourth of those making one; the number making 3 contributions is about one-ninth, etc.; the number making n contributions is about 1/n² of those making one.”

Like Western textbooks, the Soviet textbooks of informatics adopted in Cuba covered such “information laws” in depth. Their main authors, Russian information scientists and engineers A. I. Mikhailov and R. S. Gilyarevskii, quoted a peculiar passage by US information scientist and historian of science Derek de Solla Price on the distribution of publication counts: “They follow the same type of distribution as that of millionaires and peasants in a highly capitalistic society. A large share of wealth is in the hands of a very small number of extremely wealthy individuals, and a small residual share in the hands of the large number of minimal producers.”

For Cuban information scientists, who had experienced a socialist revolution and an abrupt redistribution of material wealth, this unequal distribution of informational wealth also had to be radically transformed. Among these information scientists was Emilio Setién Quesada, who had studied and worked with Freyre de Andrade since the beginning of the post-revolutionary period. Setién Quesada contested the very idea of an “information law.” In an article co-authored with a Mexican colleague, he objected to the term “law,” which seemed to imply “the identification of a causal, constant, and objective relation in nature, society, or thought.” The mathematical equations represented mere “regularities,” without expressing “the causes of qualitative character of the behaviors they describe.” Those causes were historical, not natural.

Therefore, Setién Quesada and his colleague argued, publication counts did not conclusively determine the “productivity” of authors, any more than declining citation counts indicated the “obsolescence” of publications. Cuban libraries shouldn’t rely on these metrics to make such consequential decisions as choosing which materials to discard. Traditional informatics was incompatible with revolutionary librarianship because, by treating historically contingent regularities as immutable laws, it tended to perpetuate existing social inequalities.

Cuban information scientists didn’t just critique the limitations of traditional informatics, however. They also advanced a more critical approach to mathematical modeling, one that emphasized the social complexity and the historical contingency of informational regularities. In the 1980s, when Cuban libraries were beginning to adopt digital computers, Setién Quesada was tasked with developing a mathematical model of library activity, based on statistical data, for the purpose of economic planning. But he was dissatisfied with existing models of the “intensity” and “effectiveness” of library activity, devised by Soviet and US information scientists. (In the discussion below, I include mathematical explanations inside parentheses for interested readers, following Setién Quesada’s own terminology and notation.)

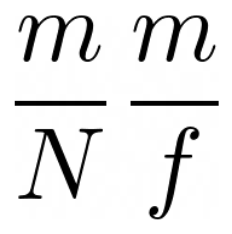

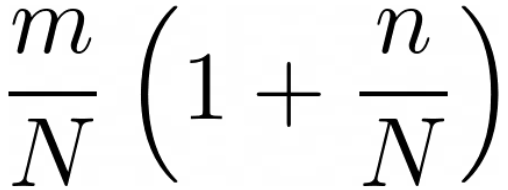

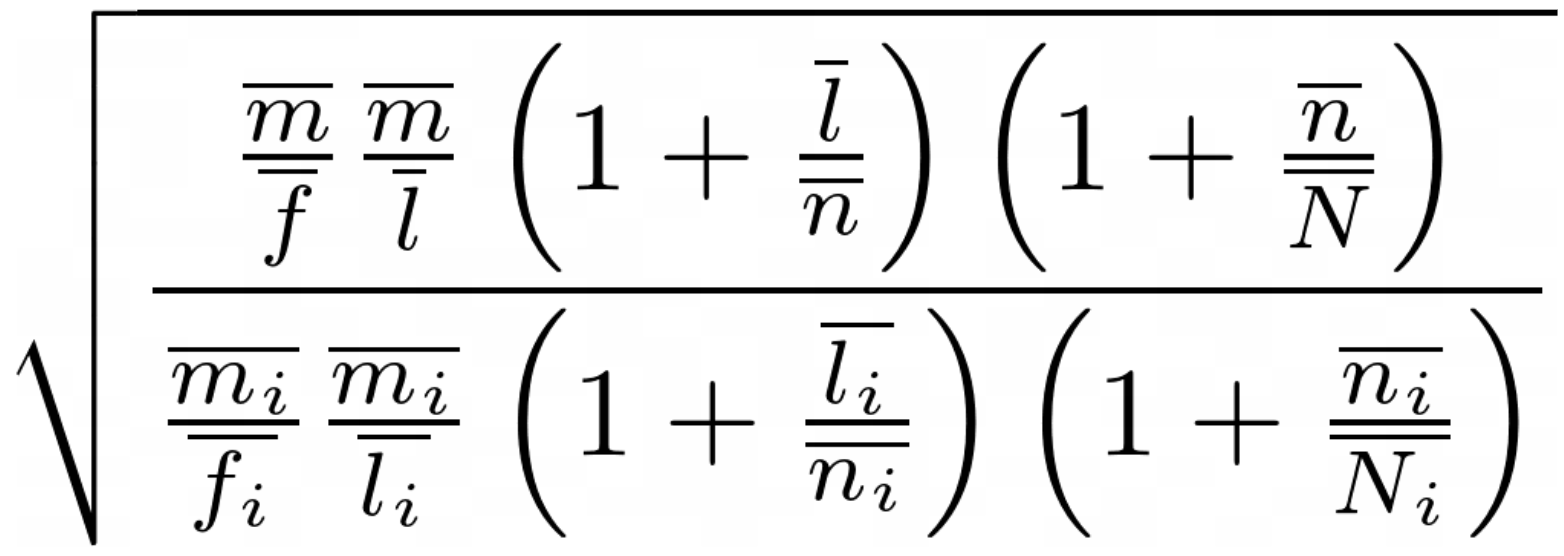

Soviet information scientists computed the “coefficient of intensity” of library activity by multiplying the “index of circulation” (the number of borrowings m divided by the number of potential readers N) by the “index of rotation” (the number of borrowings m divided by the total volume of holdings f). Meanwhile, US information scientists computed the “measure of effectiveness” of libraries, combining the index of circulation with an “index of capture” (the number of actual library readers n divided by the number of potential readers N). In contrast to these two approaches, Setién Quesada proposed an alternative “Cuban model,” which evaluated what he called the “behavior of Cuban public libraries”:

“Coefficient of intensity” (Soviet authors)

“Measure of effectiveness” (US authors)

“Cuban model”

Setién Quesada argued that “the Cuban model is more complete.” It included many more variables, all of which he considered important. For instance, the Cuban model included an “index of communication” (based on the number l of readers who use the archive), while the Soviet and US models “do not express the precise level of the author-reader social communication that happens in libraries.” Moreover, those other models “do not consider the role of the librarian in the development of the activity.” For Setién Quesada, the librarians, “together with the readers, constitute the main active agents involved in the development of this activity.” Hence in the Cuban model, every variable was adjusted relative to the number of librarians (incorporated into the adjusted variables denoted by a vinculum). Finally, the other models “do not offer an index that synthesizes the comparative behavior of places and periods.” By contrast, the Cuban model sought to facilitate comparisons of different libraries and time periods (each represented by the subscript i).

Whatever the merits and limitations of this particular mathematical model, the broader story of Cuban information science encourages us to be skeptical of the claims attached to models and algorithms of information retrieval in the present. If yesterday’s information scientists claimed that their models ranked authors by “productivity” and libraries by “effectiveness,” today’s “AI experts” claim that their algorithms rank “personalized” search results by “relevance.” These claims are never innocent descriptions of how things simply are. Rather, these are interpretive, normative, politically consequential prescriptions of what information should be considered relevant or irrelevant.

These prescriptions, disguised as descriptions, serve to reproduce an unjust status quo. Just as print publications should not be deemed obsolete and discarded from library collections on the basis of citation counts, online information should not be deemed irrelevant and ranked low in search results on the basis of “click-through rates” and ad revenues. The innovative experiments by Cuban information scientists remind us that we can design alternative models and algorithms in order to disrupt, rather than perpetuate, patterns of inequality and oppression.

A Network Theory of Liberation Theology

The Cuban experiments were supported by a socialist state. But experiments with anti-capitalist informatics are also possible in the absence of such a state. In fact, another major undertaking took place in countries that were controlled by US-backed right-wing military dictatorships.

In many Latin American countries, including Brazil after the 1964 military coup, authoritarian regimes took violent measures to silence dissidents, such as censorship, imprisonment, torture, and exile. Some of the most vocal critics of these measures were Catholic priests who sought to reorient the Church toward the organizing of the oppressed and the overcoming of domination. A key event in the formation of their movement, which would become known as “liberation theology,” was a 1968 conference of Latin American bishops held in Medellín, Colombia. At the landmark conference, the attendees learned of the dynamics of oppression in different countries, and collectively declared, “A deafening cry pours from the throats of millions of men, asking their pastors for a liberation that reaches them from nowhere else.”

How could this cry be heard? The Medellín experience inspired a group of liberation theologians, largely from Brazil, to try to envision new forms of communication among poor and oppressed peoples across the world. Their objective was conscientização, or “conscientization”: the development of a critical consciousness involving reflection and action to transform social structures—a term associated with their colleague Paulo Freire, who had developed a theory and practice of critical pedagogy. Towards that end, the theologians planned to organize a set of meetings called the “International Journeys for a Society Overcoming Domination.”

But international meetings were prohibitively expensive, which meant many people were excluded. One of the project organizers, the Brazilian Catholic activist Chico Whitaker, explained that “international meetings rarely escape the practice of domination: in general they are reduced to meetings of ‘specialists’ who have available the means to meet.” To address this problem, the liberation theologians and allied activists envisioned a system of information diffusion and circulation that they called an “intercommunication network.” This network would make available “information that was not manipulated and without intermediaries,” break down “sectoral, geographic, and hierarchical barriers,” and make possible “the discovery of situations deliberately not made public by controlled information systems.”

By “controlled information systems,” the organizers referred to the severe state censorship of print and broadcast media that had become prevalent across Latin America. Liberation theologians wanted the liberation of information, which would enable a new phase of Freirean pedagogy: from the era of “‘conscientization’ with the intermediaries” to that of direct “‘inter-conscientization’ between the oppressed,” in Whitaker’s words.

Since the modern internet was not yet available in the 1970s, the operation of the “intercommunication network” relied on print media and the postal service. The organizers set up two offices, called “diffusion centers”: one in Rio de Janeiro, at the headquarters of the National Conference of Bishops of Brazil where Brazilian bishop Cândido Padin, an organizer of the Medellín conference, served as project coordinator; and another in Paris, where Whitaker lived in exile with his wife, Stella, another Brazilian activist, because of his role in land reform planning before the 1964 military coup.

The diffusion centers received and distributed, by mail, submissions of short texts (or five-page summaries of longer texts) analyzing situations of “domination” from a worldwide network of participant organizations, connected via regional episcopal conferences in Latin America, North America, Africa, Europe, Asia, and Oceania. Whitaker emphasized that the texts should ideally be written by “those who have the greatest interest in the overcoming of domination, namely, those who are subject to it,” and should include “analysis of their own situations and the struggles that they were developing to liberate themselves from domination.” The organizers published every text that matched the basic requirements, without any editorial modification; translated each text into four languages (Portuguese, Spanish, French, and English); and mailed all texts for free to participants in more than ninety countries.

For Whitaker, the concept of intercommunication was rooted not only in “freedom of expression” but also in “liberty of information”: the ability for all participants to have access “to everything that the others wish to communicate to them and which serves the realization of the objectives which they share.” Intercommunication sought to produce radical equality: “All must be able to speak and be listened to regardless of the hierarchical position, level of education or experience, social function or position, moral, intellectual, or political authority of each.” The practice of intercommunication demanded the “acceptance to heterogeneity and of the ‘dynamic’ of conflicts that go with it,” Whitaker wrote.

Finally, intercommunication required an exercise of “mutual respect” and “openness towards the others” that reflected the Christian principle of fraternity: as Whitaker put it, “the respect for what the other thinks or does… the receptiveness to what is new and unexpected, to that which poses questions to us or challenges us, or to perspectives and preoccupations that we would have been able to leave aside because they are difficult to accept.” Despite the importance of Christian values, however, the intercommunication network was open to anyone. Some participants were non-Catholic, non-Christian, and even non-religious. Padin explained that as “children of God, we are in Christ all brothers, without any distinction.”

The Freedom to be Heard

Over the years, the intercommunication network circulated an extraordinary diversity of texts. Chadian participants examined the social consequences of cotton monoculture since its imposition under French colonial rule. Sri Lankan participants reviewed the labor conditions in the fishing industry, the profiteering tactics of seafood exporters, and the limitations of fishing cooperatives set up by the state. Panamanian participants narrated their struggle for housing and their formation of a neighborhood association. From Guinea-Bissau, a group of both local and foreign educators, including Paulo Freire, wrote about the challenges of organizing a literacy program and changing the education system in the aftermath of the war of independence. Between 1977 and 1978 alone, nearly a hundred texts circulated in the network. These were later compiled into a monumental volume, published in four languages and discussed at regional meetings of network participants across the world.

This volume featured an unusually sophisticated system of indexing. Each text had a code composed of a letter and a number; for example, the aforementioned Chadian text had the code “e35.” The letters indicated the type of text—“e” for case studies, “d” for discussion texts, “r” for summaries—and the numbers were assigned chronologically. The volume was divided into sixteen numbered sections, each about a different theme of “domination.” Section III focused on “domination over rural workers,” section IV on “non-rural workers,” section VII on “domination in housing conditions,” section X on “health conditions.”

Each text was printed inside one of the thematic sections, but since the classifications were not mutually exclusive, the index of each section also listed texts that intersected with the theme despite being from different sections. For instance, the index of section IX, on education, listed some main texts—“e4” from Thailand, “e6” from Guinea-Bissau, “e38” from the Philippines—as well as other texts from different sections, like “r3” from section X, which discussed the intersection of health and education in structures of domination. The end of the volume featured an additional index that classified texts according to “some particular categories of victims of domination”: “women,” “youth,” “children,” “elderly people,” and “ethnic groups.”

The astonishing diversity of texts circulated by the intercommunication network soon brought its organizers into conflict with conservative factions of the Catholic Church. In 1977, some readers were especially scandalized by text “e10,” submitted by a small, women-led, self-described “community of Christian love” in rural England. The text bothered conservatives not only for its explicit denunciation of “the Roman Catholic Church as an instrument of domination” engaged in “a kind of efficient and specialized ‘brain washing,’” but also for its feminist proposals, which included the refusal “to call anyone ‘father’ in a clerical context” and the commitment to “calling the Holy Spirit ‘She’ and not ‘He.’”

After a long deliberation at the Rio de Janeiro diffusion center, the project organizers decided to publish the text along with a note restating their commitment to free expression and reminding readers of the minimal requirements for publication. Still, conservative bishops complained to Vatican authorities, who were increasingly concerned by the rise of liberation theology in Latin America and beyond. Pope Paul VI, who did not sympathize with the project, sent emissaries to Brazil to intervene. The Vatican demanded that the bishops stop, claiming that the conference in Rio de Janeiro “could not take an initiative of such breadth, and had surpassed its competence by inviting other episcopal conferences to join the project.” By building a distributed worldwide network via regional conferences, the liberation theologians had bypassed the central authority of the Vatican. Despite the Vatican’s order to stop the project, a group of Brazilian organizers continued in disobedience until 1981.

Later on, former organizers reflected on the relationship between their intercommunication network and the modern internet. They did not know that in the original paper on the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP), which outlined the technology that serves as the basis of the internet, engineers Vinton G. Cerf and Robert E. Kahn had spoken of a protocol for packet “network intercommunication”—or simply an “internetwork” protocol, leading to the contraction “internet” a few months later. The paper had appeared in 1974, when the liberation theologians were planning their similarly named network.

In 1993, reflecting on the two internets, Chico Whitaker theorized that the “network” is an “alternative structure of organization,” much less common in “Western culture” than the “pyramidal structure”:

Information is power. In pyramids, power is concentrated, so also information, which is hidden or kept to be used at the right time, with a view to accumulating and concentrating more power. In networks, power is deconcentrated, and so is information, which is distributed and disseminated so that everyone has access to the power that their possession represents.

There is no doubt that Whitaker and his colleagues were prone to techno-utopianism. Their hope that technological progress would finally enable a “free” circulation of information was a fantasy, since various sorts of machine decisions and human labor, structured by political-economic conditions, always filter what information circulates and to whom. Techno-utopian conceptions of “information freedom,” whether in the Californian libertarian-capitalist version or in the Brazilian liberation-theological one, are never quite right.

Yet there is a crucial difference between the two conceptions. The Californian version of information freedom is largely limited to a particular understanding of freedom of speech. The Silicon Valley firms that manage public discourse on the internet, such as Facebook, appeal insistently to “free speech” as an excuse for their business decisions to profit from posts and ads that spread right-wing misinformation.

The remarkable innovation of the Brazilian liberation theologians is that they moved beyond a narrow focus on free speech and toward a politics of audibility. The theologians understood that the problem is not just whether one is free to speak, but whose voices one can hear and which listeners one’s voice can reach. The intercommunication network was meant to produce more equitable conditions not just for speaking, but for listening and for being heard. Ultimately, the network’s purpose was to amplify the voices of the oppressed. Today, our task is to reformulate this more critical conception of information freedom for the digital age. Information will be “free” only when the oppressed can be heard as loudly as their oppressors.

The Retrieval of History

The history of technology is too often told as a linear progression, as a series of tales of triumphant inventors, emanating mainly from North America and Western Europe. Such tales are pervasive in part because they are easy to tell. After a certain technology prevails, the storyteller can simply follow the records and narratives given by the handful of people who are already credited for its invention.

Such commonplace narratives serve important ideological functions. First, they legitimize capitalist accumulation by framing the inventor-entrepreneur’s fortune as the merited payoff for an ingenious idea. This requires erasing all other contributors to the given technological artifact; in the case of search engines, it means forgetting the librarians (whose feminized labor is never valued as creative) and the information scientists whose cumulative work over the course of decades laid the foundation for Google.

More insidiously, such narratives also serve to sanction the dominant technologies by presenting them as the only ones ever conceivable. They overlook the many possible alternatives that did not prevail, thereby producing the impression that the existing technologies are just the inevitable outcome of technical ingenuity and good sense.

If peripheral innovations like the Latin American experiments with informatics did not become mainstream, this is not because they were necessarily inferior to corporate, military, and metropolitan competitors. The reasons why some technologies live and others die are not strictly technical, but political. The Cuban model was arguably more technically sophisticated than its US counterparts. Yet some technologies are sponsored by the advertising industry, while others are constrained by a neocolonial trade embargo. Some are backed by the Pentagon, others crushed by the Vatican.

It is crucial to recover those lost alternatives, for they show us how technologies could have been otherwise—and could still become so in the future. However, these histories are difficult to retrieve. Their protagonists may remain anonymous and their records unpreserved.

No search engine pointed me to the Latin American experiments. I could never have found them through traditional methods for searching the internet. Instead, I came across subtle clues through serendipitous conversations. I was chatting with Theresa Tobin, a retired librarian at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who co-founded the Feminist Task Force at the American Library Association in 1970. She commented that after she fundraised to donate a digital computer to a Sandinista library in the 1980s, Nicaraguan librarians used it to implement a Cuban system for indexing materials.

I set out to learn more about the Cuban system, a task that proved laborious. Even the most important sources on Cuban information science are hard to find using conventional search engines and databases. For instance, despite the prominence of María Teresa Freyre de Andrade, Google Scholar does not index her main books, and Wikipedia lacks an entry on her in any language. On the other hand, the Cuban online encyclopedia, EcuRed, features an extensive article on her. I also managed to find a few initial references on Cuban informatics in SciELO, a Latin American bibliographic database. I then contacted Cuban scholars directly to ask for help.

My discovery of the liberation theologians’ intercommunication network took a similar path. When I first met Stella and Chico Whitaker at the World Social Forum in Porto Alegre, which they co-founded in 2001, I had never heard of the intercommunication network. It was only years later, when I was helping the couple donate their personal papers to a public archive, that they mentioned in passing that one of the dusty boxes in their apartment contained documents from an old project involving informatics. They were surprised I showed interest. Sometimes the best method of information retrieval is talking to people.

Many more vital ideas for alternative futures, technological and otherwise, remain forgotten in dusty boxes across the world. The repressed dreams of past struggles will not easily appear on our corporate algorithmic feeds. To recover these lost ideas, we must develop more critical methods of information retrieval, continuing the work that the Latin American experiments left unfinished. In short, we need critical search.

The project of critical search would recognize that any quantification of “relevance” is an interpretive, normative, and politically consequential act. Critical search would actively strive to increase the visibility of counterhegemonic intellectual traditions and of historically marginalized perspectives. We must build systems of information diffusion and circulation that seek to amplify critical voices and to cut across linguistic, national, racial, gender, and class barriers. Let us draw inspiration from our predecessors, and try to follow in their footsteps. Let us experiment with algorithms, interfaces, and tactics for reindexing the world anew.