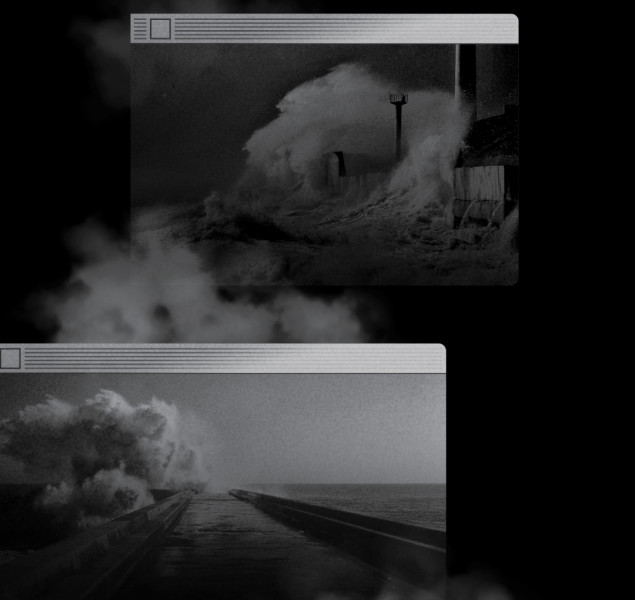

I wonder what’s taken me so long to pop the question, and why this ritual that’s been performed countless times by so many before me bears down on me like I’m the first woman in history to put a knee to the floor and offer the ring and say the words. She’ll say yes. We talked about it. When we lay beside each other, Aluna gains the power to ease the edge around momentous things, and it’s all in how she finds the right tenor, right whisper, the right circles of pressure to trace along the dips of my neck. I’ve brought all sorts of crises to her before sleep. VR recordings of tragedy filmed that very morning, from hundreds of miles away and through the dissociative lens of a drone’s 360 degree camera. Roaming tent cities trudging across the Sahara that siphon power from abandoned solar panel farms. Ocean slums sprawling off the coasts of Italy, Spain, France, sinking as their fate is decided in boardrooms graced with AC. Sea spray is everywhere it shouldn’t be, and scatters the footage into clouds of discordant pixels—that’s when Aluna pauses our replay, blinks our retinas clear. While the bedroom is at its darkest, we shift to face each other and she tells me what she thinks comes next. Never lessening the blows, but making it all feel approachable, which is exactly how she responded when I asked if we might actually spend the rest of our lives together. And she said yes.

It feels like I lost my chance. Tonight marks our first week sleeping on the shelter’s temporary foldout beds. We’d considered my SUV but it’s packed tight with all the remaining fragments of our apartment, the things that survived the flood. We gave it a shot, wedging ourselves between piles of clothing in the front seat, but Aluna couldn’t fall asleep. She didn’t complain once. She made constant shifts in her seat through the night, awkwardly reaching for my body only to be thwarted by the packed detritus of our old home.

Video floats at the shelter tent’s apex above all our heads. It plays the breakdown from every angle, accompanied by live commentary. First comes a deep whine, then a spear of pressured mist breaking through Boston’s seawall. Rapid growth from needle thin spikes of water to spiderweb cracks. A network of black spread over concrete, and freeze-frame there.

They’re calling it unprecedented. It’s become our country’s favorite word. A guy walks between our cots, offering each of us a refill from his chrome thermos. He looks confused yet determined, young enough to be a Harvard undergrad, coming out to volunteer and help the new climate refugees that huddle in the mandated shelters on his campus. We’re a couple blocks from where the flooding occurred and yet Cambridge is absolutely dry.

“She’s sad again,” Aluna says, like I can’t hear the dog’s cries for myself. It’s an incessant whimper from a few cots down, battling the mutters of a human trying to shut their pet up. If Aluna had her way she’d know the puppy’s name, who is looking out for her, the neighbors beside them who will have to endure her cries. She peers about the tent and watches as much as she can.

Since our apartment flooded, my work instruments have been reduced to a loan computer from the company. By the time Aluna and I realized what was happening, our floor swam beneath saltwater. She splayed her arms across the dining table and scooped up a swath of our electronics like a squirrel. Saving what she thought was most important to us, though in real-time, as crisis plays out, that’s so much harder to gauge. You can’t ever be sure of what’s supposed to matter. You grow up with all those educational vids about what to do, how to save yourself, and yet when evacuation sirens blare across the neighborhood all thoughts vacate. Most of us aren’t built for catastrophe.

I unroll my computer, laying it on my lap. My supervisor has given me some leeway with sign-on times for work due to, well, everything—but I still feel uncomfortable catching up on team messages thirty minutes late. I never imagined that being a climate victim would be so embarrassing. Aluna and I lived in a good neighborhood, made decent money, and were much more used to watching disaster rather than being a part of it. After the seawall breach, I didn’t know what to tell my boss except that it happened, that I wouldn’t wait and burn PTO, that I’d log on as always and work admin. Not out of loyalty to the brand, but to a lifestyle I wasn’t prepared to abandon. Besides, Aluna and I need the money. We haven’t touched our savings yet and we wanna keep it that way, so the work pays for the little things that patch our days together—like walking off campus to purchase snacks from the grocery store. Aluna buys cheap things to distribute among the children here. Her way of keeping up routine as a teacher, since most local schools are temporarily closed and she wouldn’t be much help conducting class from a refugee tent regardless.

My team’s been talking about the disaster all morning, filling up our text channel with questions and reports on how bad Boston’s been hit. Bickering everywhere, Garrett says, maintenance pointing fingers at the original construction firm, mayor’s scrambling. Good thing is no fingers pointed our way yet but.. Bottom line is the wall should’ve never failed.

Unprecedented, unprecedented.

Manager claims he doesn’t have much for me to do right now. Our division at Centra isn’t taking the brunt of the heat, none of the inquiries about damaged property or when the neighborhoods might be “fixed”—as if we can cast a spell and suck the ocean back in place. It’s hard to not glance at other refugees (a word I still find so strange to use here, so near my home) who either tap away on their own devices or blink through screens on their internal retina displays. I wonder which of them are filing the next complaint to the company I work for, and if I might swallow enough pride to do so myself. We all seem the type to be ashamed of this all, how we’re good enough to own multiple devices and line the cots with sets of clothes saved from the water, and yet none of us are second-home rich. Not enough resources to avoid the tents, but just enough to feel bad using them.

Admin tasks are the majority of my workload at Centra. Garrett and I are specifically in charge of benefits paperwork for the employees working under our relocation division, a reasonable job since the company keeps that section small. While Centra brands itself in all the climate net corporation tropes—commercials aglow with green fields, wind turbines swaying against sunset—the refugee relocation programs we helm are a side gig. That’s how it is with climate nets, a bit of a trend for corporations eager for a brand cleanup. Shove a random percentage of the budget to securing rent-controlled housing in northern, inland cities shielded from the typical forms of climate catastrophe, then offer up leases to a portion of the newly homeless. Great PR, makes the government happy that we do their work for them, and it provides everyone forced to live in tents a shard of hope.

A couple hours into my work day, Aluna rests a small bag of potato chips on my shoulder and kisses my cheek. She’s fond of a greeting with food involved because I’d probably forget to eat otherwise. As she takes a spot on the bed next to me, Aluna glances at the computer in my lap.

“You think Centra’s gonna put us up in a loft or something a little more? Maybe a whole house. They’ve got space out in Colorado or wherever for giving us some land, don’t you think? Full patio, a yard neither of us will know what to do with.”

“No thinking for me, love.” I dance my fingertips across the screen. “Only typing.”

Aluna grabs the bag of chips before they slide from my shoulder, opening them as she scoots closer. “Liar. You just don’t wanna tell me our spot in the queue, don’t deny it.”

Wherever we’re at, it’s probably so far down we shouldn’t think about it. Company gossip has gotten more frantic as it seems that our relocation system has ground to a halt. Centra’s been skimming people off the climate net division and nobody’s left the Cambridge tents with a golden ticket. You’d know if someone got a way out, the excitement and rush they’d fail to hide, but nobody here has escaped.

Something we’ve said snared the attention of the man who sleeps a cot away from us. He leans forward, locking eyes with me. His blazer hasn’t come off the whole week and it’s acquired a film of dust.

“Hey, I heard ‘queue.’ Can you check my status? Is there a way you can look at that?”

With a grimace, I shake my head.

“Sorry, doesn’t work that way. I couldn’t show you the odds if I wanted to. There’s no access to relocation logs from my department.”

“Damn. Come on, really?” He hugs himself. “If you want me to pay for it, I will. Name your price. Money’s not a problem, trust me. I’m supposed to be out of here in a few days anyway, I just want to see the queue for a plan B.”

“I don’t work relocation, has nothing to do with me. Like I said, I’m sorry—I really would, but there’s nothing I can do. We all gotta wait.”

“Everyone’s fucking waiting. That all we’re supposed to do now? Those guys who got flooded in Miami, too, just sitting there.” The man squats, eyes locked on the rubber mat below us, a kindergarten sky blue. “Nobody’s moving anymore. When’s the last time you heard someone get the golden ticket? Who’s being whisked away to safe cities? Because I don’t know anybody.”

It’s not that he’s wrong, it’s just that I have nothing to say about it. There’s nothing I could say that would fix this. As the man leaves us with the ghost of his cologne, Aluna gives my hand a brief squeeze, a pulse.

And at night, that dog starts whining more. I could turn on my night vision, but instead I lay in the dark with Aluna wedged by me, still dreaming, sharing the cot’s limited real estate. Around me are rustling blankets, murmurs. Pointless, flitting. These limp sounds rise with the dog’s whimpers, a cross-species call and response.

I think I can find a relative peace again. At least one strong enough to drift back asleep, salvage some scraps of rest before the day starts. My eyes are shut against the tent’s collective discomfort. It’s the most solitude I’m capable of carving out for myself, and for the past week it has been enough. Enough against the same sighs, the coughs, the sobs that should’ve never traveled so well across this space.

The dog’s whining swoops up an octave. I’ve never heard her so distressed—beyond distressed. A shimmering yelp scraping against my eardrums, forcing me upright. Aluna’s hands scramble up my forearm and feel out my skin. There’s nothing left except for the dog and that howl, a guttural pain.

Then she’s done. One more bark, cut short and high. She’s left us in silence undercut by shifting blankets. Our neighbors freeze and look about for the source of disruption, as if pinpointing it all might let us drift back to sleep. As if we won’t all sink back to our cots, turn along the taut stretches of nylon, curl around our partners and ourselves to find a steady beat again, something like the mattress you lost back home under tons of seawater, something that was once warm with you and whoever shared life with you. But it won’t be enough to sleep.

When the morning comes, Aluna returns to bed. I hadn’t realized she left.

“She’s okay,” Aluna says, “but shaken. Someone tried to strangle her last night, right here. We think it’s one of us.”

Everyone is much too awake. People glare at their neighbors, at the ceiling. In their little movements is stored all the dread that has no legitimate avenue for escape. Our urge for relief isn’t new, though it’s become painfully visible.

My work chat is a repeat of yesterday, gossip about whose heads are on the chopping block. Talk of a “rapid retreat” from upper echelons that none of us know how to interpret. I can’t vent to Aluna no matter how much I’d like to, not in front of the other refugees.

She drifts back and forth, out into town, buying snacks for the children and a treat for the dog. This is the first time her offers are rejected. From afar, I see parents push her away. Gentle shakes of the head, hands rising up. She’s too far for me to hear how she responds.

***

I suggest we leave at sunset. She doesn’t know how to take that. We’re exchanging messages over internal displays, eating the rations they’ve started handing out for lunch. Aluna would wait and see as she put it, staying in the shelter, till the next disaster forced us to relocate again. This is no home and yet she can barely imagine leaving it. Maybe it’s the proximity to what we lost that keeps her tethered. Cambridge’s parks, rowhouses, and stores provide a familiar urban texture, and when you drift far enough from the tents it succeeds in lulling you back to normality. It’s delusional. I work where the miracles are made, and the only thing Centra is concerned about is laying people off and minimizing damage for the PR fallout of the broken seawall—a tragedy that they refuse to claim as their responsibility, taking all distancing measures available. It will grow clearer over the coming days that there is no help on the way. Not for any of us. We have to leave the city.

And where would we go? Aluna asks. She already mentioned us hitting up friends who live near Cambridge, ones who haven’t experienced climate failure outside of the dearth of food lining the shelves. We’ve held off because that shame flares up. None of our community has the bandwidth for that type of support no matter how much we wish they could provide it. They ask us what happened, if we’re alright, how they might help, and we dodge each question enough to allow them an out. They always take it.

We can’t go to them, not now. While Boston as a whole might be running relatively fine, the pockets where they’ve shoved us will soon boil over. I sigh and send Aluna a message. Even though we’re sitting across from each other, I find a way to avoid her eyes.

There’s a spot little less than an hour out of town owned by Centra. Part of their data infrastructure, and it’s quiet. We don’t need to be there for long… Just give it time for things to settle over here, a few days at most—the SUV will hold its charge, so we won’t have any problems coming in and out. A mini-retreat?

She doesn’t even crack a smile. Right before dinner, we get up and leave. Just like that. There’s nothing for us to bring along. All that’s left of our submerged home is in our SUV, sitting beneath platinum LED streetlights.

Autopilot’s enabled for this region, though I’m quick to shut it off. The highway’s riddled with flooding issues now, and I doubt the car could keep up.

As we exit the parking lot and get on the road, Aluna and I pass the low, inflated lozenges of the refugee tents, pinned to the soil with near-invisible lines of rope. Nearly biological in their aversion to clean, sharp angles, growing out of the flat campus lawns like massive fungi. Logos adorn the sides, all the entities responsible for erecting this crisis architecture. Centra’s branding appears on the tent as a circle adorned with light rays, a flat design vision of a glowing sun. In the encroaching murk, it can’t be easily defined. The sun seems to waver in the shadows, like a pinned spider flat against the outer wall.

***

There was once a time—probably late ’50s, early ’60s—when vehicular windshield HUDs were an inescapable trend of automotive design. Glowing, transparent skins hemmed glass borders, providing location-specific updates, weather, and navigation tips. By then, every other American had a retina display, though the AR novelty of these car HUDs was pushed as if it were cutting edge. At its core, the overlays are candy-colored, highly restricted web browsers tacked to the front of our vehicles. “Futuristic” was the word that nobody wanted to use, and yet guided every step of the design process. The HUDs exist because, as we near the end of the century, they seem like they should.

The glyphs and readouts bordering my windshield begin to disappear. First it’s the weather icon, a cloud eclipsing a crescent moon, winking out. Then all the stats about the car battery. That one’s especially ironic since you’d assume the SUV’s drawing on local, in-vehicle data. Just like all the other visuals drifting away, it warns me of NO INTERNET CONNECTION before vanishing.

We’ve split from I-90 onto a lone road that twists away from the city, away from the gleam of retina-enhanced billboards that outshine tent villages sprawled beneath overpasses. Density gets a lot lighter out here. Autumn foliage flanks us on either side, swimming up to high focus in the titanium pools of our headlights. It’s been almost half an hour since we passed another car.

“If you don’t know where we’re going,” Aluna mutters, “you might want to turn back, Imani. GPS is about to go out.”

That’s concerning. It’s one of the few visuals remaining on the windshield. I squeeze her thigh.

“It’s not far love. I’ll get us there. Trust me, it’s exactly the right place for us to lay low. There’ll be better connection in the barn too, so we can keep track of how things play out in town. When it seems a bit safer we can drive back in.”

“Why would the barn have good connection if it’s abandoned?”

“These things never go fully dead.” I keep an eye out for our turn. “That said, though, Centra’s moved most of their servers elsewhere, further inland. They think they’re future proofing. All this one’s used for now is cold storage, backups of backups.”

I’ve got no doubt it has to do with the sunk-cost fallacy. Decades ago Centra spent millions to get the server farm up and running, and they can’t bear wiping the whole thing out. Funny how risk averse these corporations get in the face of unstable environmental conditions.

“Look,” I say, pointing at the growing lights on the horizon, a fluorescent wash against overcast. “That’s the suburb around the corner from it. Not much longer.”

“Good ’cause we got no reception at all now.”

Aluna’s stare hits that middle space, out of focus. She’s accessing her retinal screen and judging from the grimace, she’s not liking what she sees.

“Imani? This isn’t right. No connection whatsoever, we’re completely in the dark. Is there a dampener or something?”

“I’m… not sure. I don’t know why there’d be one active around here.”

Rising over the canopy is a gas station sign, blaring out to the night. I can’t help slowing past, getting a closer look at the metal bars meshing the windows and door. They’ve got a drone hovering at the entrance, hardened edges and matte black finish implying combat. The few cars in the parking lot give off the same energy. Tints and acute angles. I’m half-convinced we’ll glimpse an insignia of some sort, hopefully one of a private military firm instead of a paramilitary group, like the ethnostate bands that crawl through the Pacific Northwest.

The homes out here are different too. Most of us try to avoid traveling via highway, so the suburbs have become a rare occurrence in our lives. Last time I passed through was maybe a year and a half ago, and the two-story homes were adorned with the typical New England fanfare of ivy and wrought iron. A handsome weariness. Last time I came through, the internet worked. Now it’s all dark. Bars mesh over every window. It’s a stretch to call this a neighborhood, this collection of fortresses tucked away at the end of winding driveways, peeking through the forest in utter silence. If it were daytime we might even see the antennae they erected to shut down the network. All we’ve got is their absence.

“We’re okay,” I say, and Aluna doesn’t respond. I turn down the side street marked with the Centra logo, and we creep down a long gravel path.

***

It’s called the barn because it’s a massive, ugly, hulking structure that carves up the forest with gray paneling and harsh floodlights. The electrified gate swings open once it recognizes me and allows us to approach the dead server farm. Maybe not the right word there, dead. The building’s humming with vibrations and light. While there are potholes eating their way across the asphalt, and there’s not a single other car in the area, the place is still on.

Once we drive past the threshold, the car’s HUD returns in a flicker. Our connection piggybacks on Centra’s network. Aluna settles in the passenger seat.

“I’m checking the news.”

I park near the barn’s main entrance, two glass padlocked doors. Judging from the imagery of server farms I’ve seen back in the day, the aesthetics of these buildings refuse to change. They remain one step abstracted from a warehouse.

“We don’t have to stay here for too long,” I say. “Just a night or two. Just to see if things heat up in town or if we’re good.”

She nods along, but I’m not sure if it’s enough. This feels right to me, getting out, so I have to find a way to swallow the guilt. The last thing Aluna wants is to be far from the community, disengaged with helping in all those small ways. I don’t operate like that. Not to say I don’t care, but when I exchange snacks or provide some clothing, I only feel dread. I’m never doing enough. Aluna might find fulfillment in those acts, or she might hide her fear better than I do. It’s not something I’ve had the urge to figure out until now.

We lean our seats back as far as they go, crushing the remains of our apartment in the back. Each readjustment brings another plastic creak.

“Look,” Aluna says, and shares video of Southie. More drone footage, smooth like the camera’s on rails in the sky. The water has already started to lessen. All of our neighborhood’s detritus has mixed in the flood to make the ground invisible. Frothing, dark water, yet so low, getting lower… It feels odd to think of it this way, but the destruction feels pathetic. A quilt drifts from what was once a window. It’s matted with glass and other things, objects I can’t identify no matter how close the zoom gets. Whatever’s been abandoned wades through ruins that we want more than anything to return to.

I blink away the footage and turn to face Aluna.

“What do you think?”

And at first, it seems she might respond as she used to when we slept in a bed together. Aluna opens her mouth and hesitates. Her hand reaches across the cup holders and up my arm, to my collarbone, and finally the dips of my neck.

“I think we should learn how to be lost. It’s okay, or it’ll have to be. Know what I mean?”

“Want an honest answer?”

She nods. I catch her hand in my own, feel where the ring should be. I should’ve asked her already. I bought her a ring, and I don’t know where it might be buried. It could be in this car with us or tumbling down a sewer drain.

“We shouldn’t be fucked over so fast, Aluna. It’s not supposed to all end so quickly. I always thought there’d be a… I don’t know, a warning? A heads up of some sort. Like, yes, the end’s coming, as it’s been since forever, but here’s a week head start. Or even a day. I don’t know how we wake up and face all of it gone, and whatever. That’s it. We keep going.”

“I mean, you just said it. It’s always been coming. The warning call’s blared for decades, and we watched it every night. We just thought we’d be lucky.”

We can’t live off luck. One day soon, we’ll have to find a path forward. It’s not something I can think of now. Now, all I see is Aluna, her cheekbones carved through the data center’s security floodlights. For an hour more, we stay up and watch more footage from back home. The tents are not faring well tonight—actual skirmishes popping up, people who never imagined fighting for survival forced to fend for any resources they can get a handle on. I wish a wake up call didn’t involve people getting hurt.

By the time we start drifting off, we agree it’s not as bad as it could’ve been. Even from the scattered news footage, it’s clear there are people like Aluna among the tents. Lots of little things resulting in countless points of de-escalation. Though we’ll need more to recreate our homes, it’s a start. I think, next morning, we’ll head back.

***

I check the back while Aluna’s fast asleep. The trunk, too. Moving as quietly as possible through years and years of our shit, all of it bursting at the seams and threatening to fall across the parking lot. Every exhale is a puff of mist, and I blink to clear my eyes.

Journals, clothes, random pieces of silverware, actual physical books, toothpaste, blankets—I bring one out, drape it over Aluna’s body in the passenger seat, then go back to my search.

I find it wedged on the trunk floor, beneath the corner of a box. It must’ve fallen out of the case. Unmarred, a thin silver ring.

After scooting back in the driver’s seat, I hover with the ring tucked in my palm. It grows warm there, in the safety of my hand. I don’t ever want to let it go until Aluna’s ready to take it. So I’ll wait till next morning, and see what she says.