Americans will eat about two billion chicken nuggets this year, give or take a few hundred million. This deep-fried staple of the nation’s diet is a way of profiting off the bits that are left after the breast, legs, and wings are lopped off the nine billion or so factory-farmed chickens slaughtered in the country every year. Like much else that is ubiquitous in contemporary life, the production of nuggets is controlled by a small group of massive companies that are responsible for a litany of social and ecological harms. And, like many of the commodities produced by this system, they are of dubious quality, cheap, appealing, and easy to consume. Nuggets are not even primarily meat but mostly fat and assorted viscera—including epithelium, bone, nerve, and connective tissue—made palatable through ultra-processing. As the political economists Raj Patel and Jason Moore have argued, they are a homogenized, bite-sized avatar of how capitalism extracts as much value as possible from human and nonhuman life and labor.

But if chicken nuggets are emblematic of contemporary capitalism, then they are ripe for disruption. Perhaps their most promising challenger is a radically different sort of meat: edible tissue grown in vitro from animal stem cells, a process called cellular agriculture. The sales pitch for the technology is classic Silicon Valley: unseat an obsolete technology—in this case, animals—and do well by doing good.

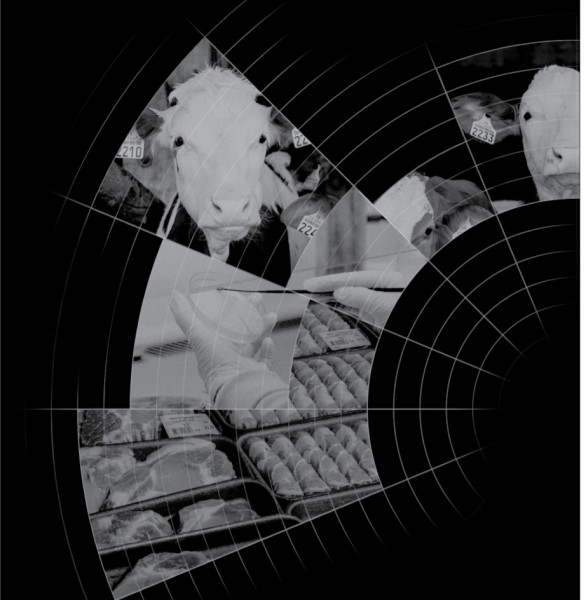

Intensive animal agriculture, which produces nuggets and most of the other meat that Americans consume, keeps the price of meat artificially low by operating at huge economies of scale and shifting the costs of this production onto people, animals, and the planet. The industry deforests the land, releases hundreds of millions of tons of greenhouse gases every year, creates terrible working conditions at slaughterhouses, and necessitates abhorrent animal treatment on farms, all while engaging in price fixing, lobbying for environmental and labor deregulation, and pushing for unconstitutional anti-whistleblower laws.

The problem is that people love eating meat, with global production and consumption growing steadily and little sign of a collective vegan epiphany on the horizon. This makes intensive animal agriculture a wicked problem: something so obviously detrimental, and yet so politically and socially entrenched, that it is unclear where reformers should even start. Cellular agriculture, however, seems to offer a potential socio-technological hack: it could eliminate much of the damage that system causes, without requiring consumers to sacrifice meat.

Long the stuff of science fiction and philosophical musing, cellular agriculture is fast becoming a reality. In December 2020, the San Francisco-based food company Eat Just debuted the world’s first commercially available cell-based meat at the private 1880 club in Singapore. Its form—a chicken nugget—was partly symbolic, partly necessary: the technology isn’t advanced enough yet to replicate a chicken’s breast, wings, or legs. But the entire animal kingdom is ripe for replication. The first cellular agriculture prototype presented to the public was a burger patty created by a research team at Maastricht University in 2013. The company that grew out of that project, Mosa Meat, is now speeding toward market release of cell-based beef. Aleph Farms, an Israeli start-up, has 3D printed a cellular ribeye steak. Shiok Meats out of Singapore is cultivating shrimp without the shrimp. Berkeley’s Finless Foods is tackling the endangered bluefin tuna. And Australia-based Vow wants to diversify beyond the most-commonly eaten species to zebra, yak, and kangaroo.

Most of this development is being carried out by a fast-multiplying number of start-ups clustered in the world’s tech hubs. They are supported by a global network of ultrawealthy investors and venture capitalists who have plowed around $4 billion into meat alternatives in the past half decade, including about $600 million into cultured meat. Richard Branson, Bill Gates, and a slew of other billionaires are investors and hype men for the technology; the Maastricht burger was funded in part by the Google co-founder Sergey Brin. But major corporations are getting in on the ground floor, with the pharmaceutical behemoth Merck investing in Mosa Meats and the meat giant Tyson Foods buying a stake in Silicon Valley’s Memphis Meats.

That private capital is working overtime to disrupt farming with synthetic biology is likely all that both boosters and critics need to know about the technology. Techno-optimists see a future of widely available “clean meat,” as ecologically and ethically superior to the original as solar power is to coal. Opponents see corporate-controlled “lab meat” that slots all too comfortably into a broken capitalist food system.

Both sides have some truth to them, but they wrongly assume that the outcomes have been determined in advance. There was nothing predestined about the forces that drove the food system to ever-intensifying mechanization, labor exploitation, and environmental ruin in the last century; it happened because of political choices both collective and individual. Similarly, we need not be prisoners of tech monopolists slapping grey “vat meat” on our plates. What we need is an analysis of the possibilities of cellular agriculture—what this novel food technology, with the right policies and investments, could make possible for consumers, workers, animals, and the environment.

Disassembly Lines

To grasp the promise and perils of cellular agriculture, we need to understand the system it might change. Our current animal agriculture policies and practices do immense damage, and uprooting them will require enormous collective effort, but history shows that the system can change radically, even in the course of a generation.

For consumers, the current food system is defined by abundance and low prices. Americans spend just under 10 percent of their disposable income on food, among the lowest rates in the world, and eat a whopping 270 pounds of meat each per year, including 122 pounds of chicken. But there’s a high price to pay for low costs. Today, billions of genetically indistinguishable chickens live and die in squalid misery in supersized facilities designed around high efficiency and low margins. Three major processing companies—Tyson, Perdue, and Koch—control 90 percent of the American market for chicken meat. The industry either functions as a monopsony, with a small number of buyers imposing prices and conditions on producers, or in some cases is vertically integrated so that Big Chicken directly controls most of the value chain.

This gives the industry tremendous economic power over farmers, workers, and consumers. Farm owners on contract with major processors are forced to compete so hard against one another that many are lucky if they barely break even. Chicken processing is grueling, low-paid, dangerous work on high-speed slaughter lines that kill 140 birds per minute. A 2015 Oxfam report on the industry told stories of workers forced to wear diapers on the line because they were denied bathroom breaks, and of others crippled by repetitive motion injuries. Meanwhile, chicken giants including Tyson and Pilgrim’s Pride recently settled nine-figure lawsuits for price-fixing brought by supermarkets, restaurants, and individual consumers. The size and wealth of these companies has also given them remarkable political heft. One of the most potent recent examples of this came in April 2020 when, at the industry’s urging, then-President Donald Trump invoked the Defense Production Act to keep slaughterhouses open, even as thousands of workers fell ill with Covid-19.

Meanwhile, cramming animals into factory farms and clearing land for more feed crops has increased the likelihood of outbreaks of zoonotic diseases, such as H1N1 swine flu or Covid-19. The system disables and kills even more people through non-infectious diseases: over the past sixty years, changes in diet have contributed to extraordinary increases in the number of Americans with obesity, diabetes, and heart conditions.

We arrived at such a grim place for two reasons. The first is the application of capitalist pressures for efficiency and the tools of industrial management to agriculture, a process that has been happening for at least two centuries. The second is that the politics of food in the United States have been shaped at almost every level by agricultural policies that have created an endless trough of subsidies, but barely any labor or environmental regulations. The whole system has been engineered primarily for the benefit of the owners of farmland and huge agribusiness firms, and at the expense of the public.

Nowhere are these economic and political histories more visible than in the case of meat. Animal slaughter was industrialized by the meatpackers of late-nineteenth-century Chicago, where 40,000 mostly low-wage Black and immigrant laborers slaughtered millions of cattle and swine every year on so-called “disassembly lines.” This high-volume model required standardized inputs—both grain and the animals that ate it—suitable for industrial processing. The creation of those inputs was supported by the US government, which early in the twentieth century launched programs designed to facilitate intensive agriculture—to turn every farm into a factory, as the historian Deborah Fitzgerald puts in. This included providing education and research support through land grant universities, tax breaks and subsidies for both beef and feed, better credit services and crop insurance, and access to improved farm technology.

These dynamics eventually led to the advent of factory farms after World War II. Although chickens weren’t a staple of the American diet until the postwar period, they proved to be particularly well suited to industrialization because they reproduce quickly and their size and egg-laying capacity are easily modifiable through breeding. Meat companies set about creating a market for chicken meat through relentless advertising campaigns, and the factory-farming model soon spread to pigs and influenced the development of ever-larger feedlots for cattle. The environmental health scholar Ellen Silbergeld has described this as the “chickenization” of agriculture.

Smart progressive critiques of this system abound, but most alternatives to it involve trying to hit reverse by breaking up the food giants and downsizing and diversifying America’s farms. But antitrust policy alone won’t address the harms to animals, labor, or the environment of contemporary animal agriculture. In reality, breaking up big operations could simply generate more, if maybe slightly smaller and slower factory farms. As for actually small farms engaged in more holistic agriculture, the theory is that they are more environmentally sustainable, protect jobs, and keep local foodways stocked with juicy heirloom tomatoes and humanely raised beef. But the idea that building an agricultural system around small farmers is economically viable and will benefit the majority of the population is a lovely idea that is often assumed without evidence. Many people don’t necessarily want, can’t afford, or don’t have access to organic, free-range, farm-to-fork meat and produce. What they can get are nuggets. And proponents of going small often struggle to explain how their ideas can be enacted at a scale large enough and at a low enough price to challenge the status quo, and to do so in a timeframe that responds to our ongoing ecological crisis.

Meanwhile, experts in the environmental impacts of the food system mostly concur that we need to eat way less meat. Some propose vegetarian and vegan diets as solutions. Even those that allow some meat eating recommend steep reductions, especially in the Global North. However, there are no signs that anything except outright bans on factory-farmed meat can achieve the required cutbacks, and that, for now, is a political non-starter.

This is where cellular agriculture comes in. The thing that could help solve the chickenization of our food system is not pasture-raised hens, but mass-produced chickenless nuggets.

A Suitable Medium

In 1931, Winston Churchill proclaimed that technology would one day allow humans to “escape the absurdity of growing a whole chicken in order to eat the breast or wing by growing these parts separately under a suitable medium.” As recently as the late 1990s, the remark could be cited as an example of the futility of futurology. Over the past half century, though, a rapid development of biotechnology and medical science has made cellular agriculture a reality. Stem cells, the basic building blocks of most organisms, were identified in the 1960s, growing in vitro muscle tissue became possible in the 1970s, and the first peer-reviewed research on the possibility of in vitro meat production was finally published in 2005.

Despite being cutting edge biotechnology, cellular agriculture is a fairly straightforward process. It begins with stem cells, usually harvested from live animals via biopsy. The cells are placed in a bioreactor, a temperature and pressure-controlled aseptic steel vat filled with a nutrient-dense growth medium that is basically a broth of sugars and proteins. Under these conditions, the cells proliferate and differentiate to form tissue. Fresh from the bioreactor, you’ll have an edible, if not yet appetizing substance known in the industry as “wet mass,” which must then be processed in various ways to produce nuggets, ground beef, and so on. Mimicking more complex cuts of meat—a filet mignon, say—requires additional techniques, such as growing muscle and fat cells on carefully-constructed “scaffolds” made of a material like collagen. It’s structural engineering, but at a microscopic level.

The potential benefits of this technology are manifold. Extrapolating from current small-scale processes is tricky, but most analyses of cellular agriculture suggest that it will use far less land and water, and have a smaller carbon footprint, than beef and dairy. If powered with clean energy—a big but not implausible if—it can become less environmentally impactful than chicken and pork. By cutting animals out of the value chain, it would not only prevent the torture and killing of billions of creatures every year, it would also greatly reduce the risk of diseases spreading from animals to humans (and then on to other humans). Cellular fish, if it could displace conventionally caught fish, could have even greater ecological impacts by protecting endangered ecosystems and preventing the widespread plastic pollution, including items such as discarded nets, for which the fishing industry is responsible.

Rendering slaughterhouses obsolete would also end their inherently abusive labor practices. The labor required to culture meat is highly technical and involves carefully monitoring, maintaining and adjusting bioreactors without compromising the fragile aseptic environments that cell growth requires. That’s the polar opposite of the fast-paced slaughter and dismemberment labor that results in, on average, two amputations of hands, fingers, feet, or limbs per week in the US. This means that not only could cellular agriculture factories offer substantially better-paying jobs than slaughterhouses, but that they would also be considerably safer and healthier work environments.

There is a parallel push to develop plant-based animal product alternatives. Given their capacity to use already existing technology, widely grown plants, and operate at scale while reducing price quickly, these food products are a better bet than cellular agriculture to challenge the conventional animal agriculture industry. The market for these plant-based facsimiles is slated to grow to upwards of $75 billion globally over the next five years. But, ultimately, the companies behind them are offering artful imitations that they hope consumers will wind up choosing over meat. Cellular agriculture produces real meat, allowing the technology to take the $1 trillion global meat industry head-on. It does all this by, as a tagline for the alternative-protein-promoting NGO Good Food Institute goes, “taking ethics off the table,” relying on market mechanisms and appealing to consumer choice. That limits its potential to overturn the entire industrial food system—cellular agriculture won’t, by itself, solve the problem of agribusiness concentration or increase workers’ wages—but substantially improves its chances of disrupting factory farming. It’s a moonshot that just might land.

Cellular Nuggets

This vision of cellular agriculture seems like just the sort of boosterism that Silicon Valley loves to inspire and exploit. To a growing number of critics, the enterprise smacks of “solutionism,” the foolhardy belief that technology can sidestep thorny social and political problems. For some scholars of technology, cellular agriculture is yet another exercise in “ecomodernist techno-optimism.” They argue that it is blind to the fact that “actual modernisation has entailed very real, and sometimes violent, impacts for people and societies to be modernized,” as the Uppsala University geographer Erik Jönsson put it. Many would prefer if everyone simply went vegan or vegetarian.

There are valid concerns that Silicon Valley and food corporations could use technologies like cellular agriculture to tighten their control over the food supply and greenwash noxious agricultural capitalism. Current meat culturing techniques and stem cell lines are valuable intellectual property, closely guarded by armies of patent attorneys and non-disclosure agreements. Critics worry that the result will be an industry that replicates precisely the opacity and lack of accountability of what it aims to replace. To them, cellular agriculture embraces the worst parts of the current food regime: mass-produced, nutritionally dubious nuggets sold at homogeneous fast food joints.

There are three responses to these challenges. The first is that the potential benefits of cellular agriculture outweigh all these costs. If the technology can dramatically diminish the production and consumption of conventional meat, even if it does so using the tools of financialized, neoliberal agri-capitalism, this is ethically and ecologically preferable to the status quo. Put differently, to suggest that a world of cell meat and one of factory farms are remotely comparable is to lose all sense of perspective on the food system.

The second is that cellular agriculture at scale could help restructure agricultural land use by reducing demand for animal feed, thereby opening up the space for more progressive food politics. If a government-financed land bank purchased even a small fraction of the 800 million acres currently dedicated to feeding animals in the US, it could resell millions of acres of land at favorable terms for bold new uses: establishing agro-ecological and regenerative farms that strengthen local foodways; supporting community and worker-owned farms; providing land to people from communities that have been historically dispossessed and excluded from owning land; returning lands to tribal nations; rewilding and conservation initiatives. Many of these ideas are championed by critics of cultured meat, who often suggest it is incompatible with the holistic, ecological sensibilities of slow, small and local. But all of these ideas become more feasible in a world with commercially viable labriculture.

Finally, there’s nothing inherent to cellular agriculture technology that favors venture capital or restrictive intellectual property regimes. Those who want cellular agriculture to live up to its lofty potential shouldn’t just be worried about the malignant influence of capital, they should be finding practical ways to limit it. What’s needed is the political vision and energy to liberate this technology from the grips of corporate stakeholders, and to use it for the radical project of improving the human and animal condition around the world.

But if cellular agriculture is going to improve on the system it is displacing, then the critics are right: it needs to grow in a way that doesn’t externalize the real costs of production onto workers, consumers, and the environment. There are serious questions about whether production can scale up safely and affordably, and some cellular agriculture practices need to be cast aside. For instance, many companies’ current production techniques, including the ones Eat Just used for its nuggets, use fetal bovine serum as a cell growth medium, which is harvested from the blood of cow fetuses during slaughter. But, now that we have several proofs of concept for cell meat, scale may be as much a social and political question as a purely technical one.

While some cellular agriculture research is being carried out at public universities with support from NGOs, most research and development is being done privately. Substantial capital is needed for research, development, and commercialization. But that the private sector sees potential in a technology that governments have mostly ignored is fundamentally a political problem. What we need are public institutions that can both nurture cellular agriculture and rein it in with public investment, regulation, and licensing. It is perfectly plausible that private firms flush with venture capital will find ways to scale and sharply reduce the costs of cultured meat. But they will almost inevitably do so by structuring their research programs and supply chains to maximize investor value, rather than social welfare.

The challenges to achieving scale and affordability are substantial. A reliable independent analysis for Open Philanthropy estimated that to be commercially viable, cultured wet mass would need to sell at around $25 per kilogram. Current culturing techniques could put it at around $37 per kilogram. This creates a paradox. Cultured meat at its current level of development is best suited to replace the most mass-produced, standardized, readily available meat: the chicken nuggets. But the Eat Just nuggets were $17 a plate, a price that would flop on the mass market and that may have been significantly discounted for promotional purposes. Chicken nuggets are far cheaper than $25 per kilogram, which is closer to what you might pay for free-range beef. To encourage mass uptake of cell meat, it will need to become much cheaper.

Perhaps the best way to overcome these challenges is to deploy the same strategy that the government used to industrialize farming a century ago: invest robustly in research and development through public universities, national labs, and generous subsidies. Between talk of the Green New Deal and the Biden administration’s ambitions for comprehensive climate change policy, the window for public investment in environmentally responsible technology is unusually wide. Substantial and ongoing government investment in cellular agriculture could be a part of whatever legislation emerges. Think ARPA-E, the government’s clean energy tech incubator, but for novel food products.

This could not only prevent the redundancy of small startups developing similar technologies behind closed doors, but also lower barriers to entry into the industry. It could facilitate cooperation with regulators, transparent scholarly analysis, and the establishment of industry standards, such as a moratorium on fetal bovine serum. Federal regulations and licensing agreements should require that cultured meat facilities are unionized workplaces and that qualified workers displaced from the conventional meat industry be given preference in hiring. The intellectual property developed this way would then, ideally, remain in the public trust and be farmed out to the private sector, which would commercialize a food product rather than patent food production.

Most critical visions of cellular agriculture are dystopian: unaccountable corporate giants force-feeding a captive population with fake meat. Ironically, that describes the food system we already have. A world in which the factory-farmed nugget is replaced by the bioreactor-brewed nugget would be a monumental win for animals and the environment. If tied to progressive industrial and agricultural policy, it could also be a win for labor, public investment, land use, and champions of alternative foodways. Chicken nuggets might represent everything that’s wrong with our current food system, but cellular nuggets can help build a more sustainable future.