My father, an administrator by profession, typically concluded his workday at two thirty in the afternoon. His homecoming was often delayed until three thirty or four. As a young child, the moments I spent waiting for him, tethered to the suspense of his arrival, were as countless as grains of sand on the beach. Upon spotting him, I would burst forth in a jubilant run, meeting him halfway in our shared anticipation.

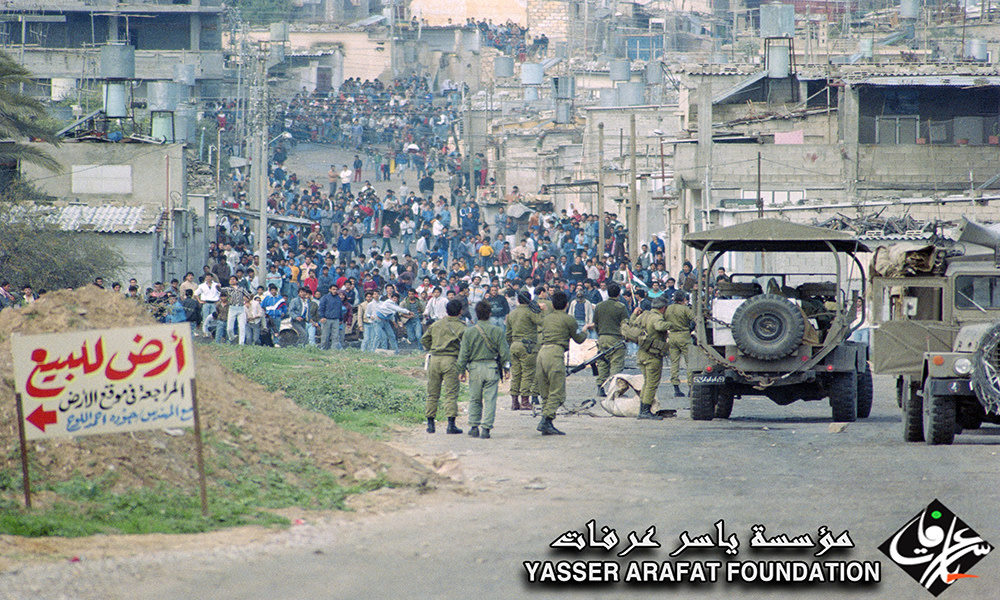

Suspended against the gritty backdrop of the First Intifada, a ubiquitous figure of a man coursed through its veins—one whose visage was etched with suffering. This man was an embodiment of every Palestinian’s experience.

On one particular autumn day, a capricious wind had commandeered the atmosphere, skipping and pirouetting through the streets, though it stopped short of summoning the rain. Its presence was evident in the choreography of the eucalyptus trees around us, their limbs swaying in a graceful waltz. The rustling foliage composed an ephemeral symphony, compelling me to believe, as a child, that the trees were performing a dance for the wind. Yet on this day, my mother exercised her veto, preventing me from awaiting my father.

In the safety of our home, the tension hung heavy in the air, like a fog that clung to the ground. My mother sighed deeply, as though attempting to exhale a burdensome thought that had nestled itself within her heart, murmuring, “When will your father get home?” Her question was soon answered by the creaking sound of the door and my father’s voice echoing through the hallway: “The Israeli soldiers are here.”

His voice carried an undercurrent of anger and worry. Summoning my mother, he commanded, “Come here, just for a moment.” She complied, disappearing for a fleeting moment before rushing back, the whirlwind of her anxiety ruffling the calm of the room. Hastily donning her headscarf and dayyer, a long, loose black skirt women in Gaza used to wear in the seventies and eighties. she beckoned me with a hurried, “come with me.” I allowed her to guide me, her urgent grip pulling me along as we raced east toward the assemblage of young men and teenagers hurling stones and curses at the Israeli soldiers who stood at the other end of the street. I was guided by my mother, my neck craned westward in the direction of the soldiers. I was scared.

As we waded into the swirling chaos, my mother was a storm of emotions, repeatedly whispering a fervent prayer, “Allah yustur! Allah yustur!” Upon reaching the front lines, she darted into a nearby shop, imploring the shopkeeper to warn the youth about the soldiers approaching from the fields. A small child was dispatched to relay the information to the young protestors, who were like deer oblivious to a prowling lion.

“Give me two packs of cigarettes,” my mother told the shopkeeper, promising to pay the next day. I left her side momentarily, drawn toward the abrupt silence that had descended. The once noisy and crowded space was eerily deserted. In the distance, I spotted two jeeps and a brigade of soldiers, an ominous sight that prompted me to return to my mother and grasp her hand.

The deserted street felt like a canvas wiped clean, with only my mother and I left as the remaining strokes of a forsaken painting. As we trudged home, a flurry of questions whipped through my mind, fueled by the disconcerting quietude. We were alone—but why? What had sparked the fear in the protestors that had caused them to scatter? Where were the soldiers of whom my mother spoke?

Upon reaching home, we found my father absorbed in cutting and hammering wood. As he gratefully accepted the cigarettes from my mother, she retreated into the kitchen, murmuring another “Allah satar” as she busied herself with brewing tea.1

Given that my father had quit smoking months ago and had a stock of cigarettes in our own shop, the sight puzzled me. I trudged back to the street in an attempt to ascertain what was going on. As I watched, my heart pounded like a war drum. I could see the soldiers drawing closer, and I could feel my fear solidify. “They are coming, they are coming,” I blurted out, my foot tapping anxiously against the ground. But my father simply pulled me into his arms, whispering reassurance.

He spoke to the officer in Hebrew while I held my breath, paralyzed by fear. He then disappeared into the shop and returned with two cans of Coca-Cola. The soldiers were everywhere, encircling the place. “La, la,” which in Arabic means “No, no.” The officer declined. My father replaced the cans and presented a pack of Imperial cigarettes. The scene unfolding outside was observed by my mother as well, her face a battlefield of fear and fury.

Suddenly, the officer erupted in laughter, a contagious sound that rippled through the ranks, turning the tense moment into a spectacle of bizarre humor. With a dismissive wave and a jovial “Khalas, khalas” (“Enough, enough”), he signaled my father to stop. As the tension dissipated, the echo of their laughter hung in the air, a bizarre end to an inexplicably strange day.

Years later, my father would reprise that day’s narrative again and again, each retelling imbued with an unmistakable pride. His role in what had in fact been a momentous event held an indelible place in his heart. As he had been making his way home that fateful day, he had overheard a fragment of a conversation from a soldier’s walkie-talkie. The officer, speaking in Hebrew, had been strategizing on how to ambush the defiant young men of our neighborhood, and directing another group of soldiers coming from the back fields behind the youth who were, at that moment, venting their frustrations by hurling stones and spewing invectives at the soldiers.

Understanding the implications of the officer’s words, my father had hurried home to apprise my mother of the situation. She had swiftly sprung into action, warning the unsuspecting activists of the impending danger. When I later inquired about her curious procurement of two cigarette packs and her decision to take me along, she offered a simple explanation: “If the soldiers intercepted me on the way, I would’ve said I was taking you to your uncle. And on the way back, I could justify my journey by saying I was buying cigarettes for your father.” The conviction with which she stated this, even years later, was as defiant as a flag waving in the face of a storm. And when I asked her what she would’ve done had her ruse failed, she simply said, “The game would’ve been over before it even started, had I not taken that risk.”

When the soldiers approached my father, it had been a test of his comprehension of Hebrew. The officer had asked him, “Ata midaber Ivrit?,” questioning if he spoke Hebrew. Each time my father recounted this, his face would split into a wide grin, as if the memory was as fresh as morning dew. His voice resonating with a touch of drama, he’d say, “They thought they could play me for a fool!” A hearty, echoing laughter would accompany his words. He continued, “The first time they asked, I brought them Coca-Cola. The second time, I offered them cigarettes.” His actions reminded me of an old man’s wisdom I once heard: What is life’s purpose if not to alleviate the hardships of others? My father had willingly placed himself in the line of fire to protect our youth and their families from possible imprisonment or even death. “The sons of dogs thought I was a fool,” he’d chuckle.

Neither of my parents conceded defeat to the soldiers that day, for in their hearts, they had yet to conceive of the possibility of losing. This resistance was their beacon, illuminating the path of defiance in the face of overwhelming odds. Their courage was like a sturdy ship, defying the raging storm and holding steadfast to its course.

1. The phrase Allah satar is used in the Arabic Palestinian Gaza dialect, uttered when something bad has not occurred, meaning “God has prevented the worst from happening.”