In the future that was imagined during the Obama years, the technology industry was one of the most valiant heroes. As the confetti settled in 2008, Obama was celebrated as the “first internet president.” He was as natural in the medium as Kennedy had been in television. Four years later it was the campaign’s unprecedented data analytics strategy—one which mined personal information on tens of millions of Americans to target its messaging—that was framed as the secret of the president’s re-election.

Obama was hailed as a modern, progressive figure. He was bringing Silicon Valley innovation into the heart of government. With that smile and those smarts, what could go wrong?

Of course, in 2016, everything did go wrong. Hillary Clinton’s precision-guided electioneering efforts came up short. Donald Trump was elected president—thanks to many of the same targeting techniques pioneered by Obama, and a Russian-fed misinformation campaign across Facebook and Twitter. Ever since, Big Tech’s political fortunes have dimmed. It is now at risk of joining the ranks of Big Tobacco, Big Pharma, and Big Oil as a bona fide corporate pariah.

Today, a growing number of people are thinking about how to regulate Big Tech. Think tanks are studying the complex interactions between social and technical systems, and proposing ways to make them fairer and more accountable. Journalists are investigating how platforms and algorithms actually function, and what’s at stake for people’s lives.

But while all of this has been crucial in refocusing the public conversation, it needs to go further. We won’t fix Big Tech with better public policy alone. We also need better language. We need new metaphors, a new discourse, a new set of symbols that illuminate how these companies work, how they are rewiring our world, and how we as a democracy can respond.

Imaginary Friends

Tech companies themselves are very aware of the importance of language. For years, they have spent hundreds of millions of dollars in Washington and on public relations to preserve control of the narrative around their products.

This clearly paid off: media coverage of the industry was largely favorable, until the 2016 election forced journalists to ask much more critical questions. The shift in sentiment has put the industry on the offensive and propelled lobbying spending to new heights, with Google paying out more than any other company in 2017.

In its public messaging, Facebook describes itself as a “global community,” dedicated to deepening relationships and bringing loved ones closer together. Twitter is “the free speech wing of the free speech party,” where voices from all the world can engage with each other in a free flow of ideas. Google “organizes the world’s information,” serving it up with the benevolence of a librarian.

However, in light of the last election and combined market valuations that stretch well into the trillions of dollars, this techno-utopian rhetoric strikes a disingenuous chord.

What would a better language look like?

Most of the regulatory conversations about platforms try to draw analogies to other forms of media. They compare political advertising on Facebook to political advertising on television, or argue that platforms should be treated like publishers, and bear liability for what they publish. However, there’s something qualitatively different about the scale and the reach of platforms that opens up a genuinely new set of concerns.

At last count, Facebook had over 200 million users in the United States, meaning that its “community” overlaps to a profound degree with the national community at large. It is on platforms like Facebook where much of our public and private life now takes place. And, as the election makes clear, there is a substantial public interest in how these technologies are used. Their dominance means that a few big companies can determine what free speech and free association look like in these new, privately owned public spheres.

The ground upon which politics happens has changed—yet our political language has not kept up. We know that we look at our phones too much and that we’re probably addicted to them. We know that basically every aspect of our life—from our passing curiosities to our most ingrained habits—are recorded in private databases and made valuable through the obscure alchemy of data science.

But we don’t know how to talk about all of this as a whole or what it really adds up to. We lack a common public vocabulary to express our anxieties and to clearly name what has changed about how we communicate, how we relate to other people, and how we come to have any idea what’s going on in the world in the first place.

The work being done by experts, insiders, and policymakers—whether in the form of the EU’s new regulatory regime to govern personal data, the General Data Protection Regulation, or various conversations within the tech community—is necessary but not sufficient. For a durable and democratic response to the power of platforms, we need a shared set of concepts that are rich enough to describe the new realities and imaginative enough to point towards a meaningfully better future.

The Octopus

The biggest insight in George Orwell’s 1984 was not about the role of surveillance in totalitarian regimes, but rather the primacy of language in shaping our sense of reality and our ability to act within it. In the book’s dystopian world, the Party continuously revises the dictionary, removing words as they try to extinguish the expressive potential of language. Their goal is to make it impossible for vague senses of dread and dissatisfaction to find linguistic form and evolve into politically actionable concepts.

If you can’t name and describe an injustice, then you will have an extremely difficult time fighting it. Making the world thinkable to a democratic public—and thus empowering them to transform it—is a revolutionary act.

In the late nineteenth century, the United States was in a situation similar to today. The rapid rise of industrialization changed the social fabric of the country and concentrated immense power over nearly every facet of the economy in the hands of a few individuals. The first laws to regulate industrial monopolies came on the books in the 1860s to protect farmers from railroad price-gouging, but it wasn’t until 1911 that the federal government used the Sherman Antitrust Act to break up one of the country’s biggest monopolies: Standard Oil.

In the intervening fifty years, a tremendous amount of political work had to happen. Among other things, this involved broad-based consciousness building: it was essential to get the public to understand how these historically unprecedented industrial monopolies were bad for ordinary people and how to reassert control over them.

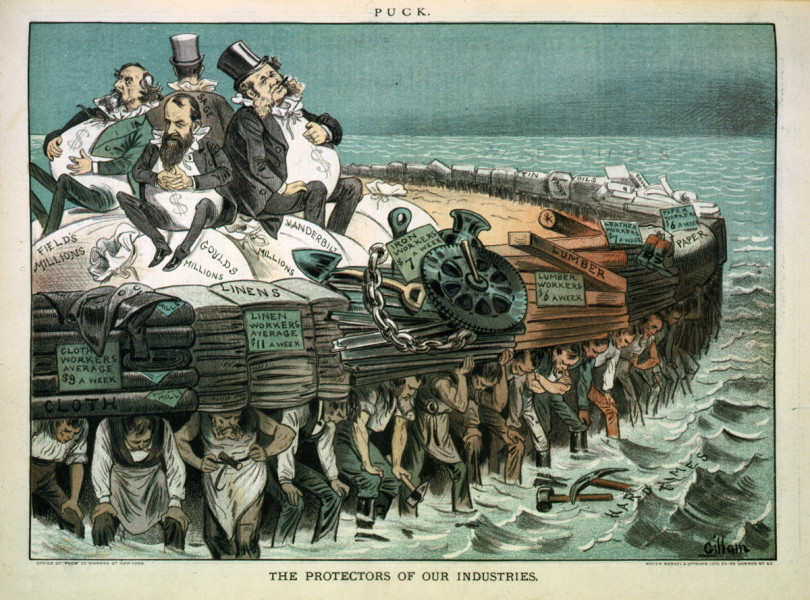

Political cartoons offered an indispensable tool in this imaginative struggle by providing a rich set of symbols for thinking about the problems with unaccountable and overly centralized corporate power. Frequently pictured in these cartoons were the era’s big industrialists—John Rockefeller, Cornelius Vanderbilt, Andrew Carnegie—generally pictured as plump in their frock coats, resting comfortably on the backs of the working class while Washington politicians snuggled in their pockets. And the most popular symbol of monopoly was the octopus, its tentacles pulling small-town industry, savings banks, railroads, and Congress itself into its clutches.

The octopus was a brilliant metaphor. It provided a capacious but simple way to understand the deep interconnection between complex political and economic forces— while viscerally expressing why everyone was feeling so squeezed. It worked at both an analytical and an emotional level: it helped people visualize the hidden relationships that sustained monopoly power, and it cast that power in the form of a fearsome monster. Conveyed as a lively cartoon, its critique immediately connected.

Think Different

What would today’s octopus look like?

In recent years, the alt-right has been particularly effective at minting new symbols that capture big ideas that are difficult to articulate. Chief among them, perhaps, is the “red pill,” which dragged the perception-shifting plot device from The Matrix through the fetid and paranoid misogyny of “men’s rights activist” forums into a politically actionable concept.

The red pill is a toxic idea, but it is also a powerful one. It provides a new way to talk about how ideology shapes the world and extends an invitation to consider how the world could be radically different.

The left, unfortunately, has been lacking in concepts of similar reach. To develop them, we will need a way of talking about Big Tech that is viscerally affecting, that intuitively communicates what these technologies do, and that wrenches open a way to imagine a better future.

A hint of where we may find this new political language recently appeared in the form of the White Collar Crime Risk Zones app from The New Inquiry. The app applies the same techniques used in predictive-policing algorithms—profoundly flawed technologies which tend to criminalize being a poor person of color—to white-collar crime.

Seeing the business districts of Manhattan and San Francisco blaze red, with mugshots of suspects generated from LinkedIn profile photos of largely white professionals, makes its point in short order. It seems absurd—until you realize that it is exactly what happens in poor communities of color, with crushing consequences. What if police started frisking white guys in suits downtown?

Much like the political cartoons of the nineteenth century, the White Collar Crime Risk Zones app is effective because it uses the vernacular language of software. It functions as a piece of rhetorical software: it’s not designed to collect data or to sell advertising, but to make an argument. And while software will never be the solution to our political and social problems, it may, to hijack a slogan of Big Tech, at least provide a way to “think different.”